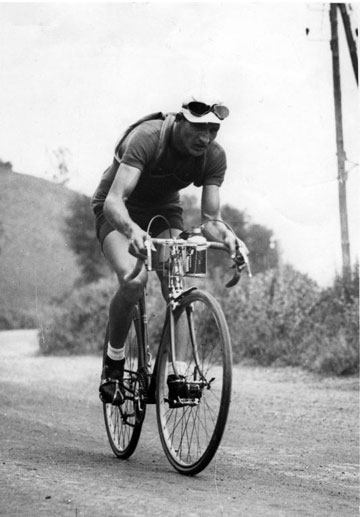

It is among the most modest of gravestone inscriptions, stating only: Gino Bartali — July 18,1914- May 5, 2000. This wasn’t to say that Bartali hadn’t won numerous championship medals for his cycling excellence, including the Tour de France and the Giro d’Italia. Nor was it because this Italian icon hadn’t used his fame and skillset to smuggle false documents inside his bike to help save over 800 Jews from being captured by the Nazis during WWII—despite the very real risks to his own life. The fact is– he actually did do all of the above. But his extraordinary life of accomplishment and altruism was above all cloaked in humility. This perhaps is why his gravestone gives no indication of his heroism. He never considered himself to be a hero; rather just a man who worked hard at what he did, and who did the right thing in the face of injustice.

In the documentary “My Italian Secret”, Bartali’s son explained that his father believed medals and trophies were bestowed to one on earth and thus should remain on the earth. He also believed that boasting about doing good deeds was akin to profiting from the souls of those who suffered.

In this day and age of social media self-promotion in order to win as many “thumbs-up” as possible, it is not uncommon to see posts bragging about one’s good deeds as a way of seeking public validation or admiration for prosocial acts; aka acts of kindness and altruism. A few “composite” examples, might read like the following:

“Felt great to help an elderly gentleman place his groceries in the trunk when I saw he was having a hard time lifting the bags himself.”

“So blessed to have been able to buy my colleagues lunch today and see the delight on their faces.”

“Nothing like paying it forward, like I did today when in the doughnut drive-through I told the cashier to deduct the next person’s order from my credit card.”

“Math nerd that I am, I actually volunteered to be a math tutor at a school for those less fortunate.”

Of course, we should commit to doing “random acts of kindness” as the popular bumper sticker read from a few years back. There are so many opportunities to do something good for someone else on any given day. Most all of them involve no personal risk to life or limb, as was the case with Gino Bartali. We should step up to the plate and welcome tasks that make the world a better place without thought of seeking praise or recognition. Altruism after all, is simply part of being a good human being, and cheerfully lending a helping hand is the right thing to do.

Consider the perspectives of Roman philosopher Seneca, contemporary research findings, or even the Bible itself:

- The stoic philosopher Seneca of ancient Rome believed that virtuous actions often require that personal desires take a back seat, that fear not be an obstacle, and that bravery and justice should guide us. We should consider good deeds as if they were not just mere tasks, but rather orders of which we follow without complaining how hard, how hazardous, or what setbacks we must encounter along the way.

- In Matthew 6:1 of the Bible it is written: Take heed that ye do not your alms before men, to be seen of them: otherwise ye have no reward of your Father which is in heaven. [2] Therefore when thou doest thine alms, do not sound a trumpet before thee (…)

- Research findings indicate that when someone broadcasts their good deeds to others, it may not have the effect it was intended it to have—e.g., to make an altruistic impression. Bragging about prosocial behavior, especially when someone is already known to be altruistic can actually have the opposite effect: That person may be perceived as selfish, rather than generous. (Conversely, a person whom others don’t typically think of as generous, may benefit from a bit of self-promotion.)

In 2006 Italy’s then- President Carlo Ciampi recognized Gino Bartali with The Gold Medal of Civil Value. In 2013 the State of Israel named him Righteous Among the Nations, an honor given to non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust by the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem. He never lived to accept either of these prestigious awards in the flesh, but my hunch is, he wouldn’t have been too concerned about that. It was his humanitarian instinct for doing the right thing that guided him, his bravery was not motivated by the expectation or of awards, recognition or praise. Bartali was not alone among the many Italians who risked their own lives to save the lives of innocent fellow human beings who were being unfairly persecuted because of their Jewish faith during one of the darkest periods in history. Prosocial acts done without expectation of anything in return, are like lights that disperse that darkness.

Bartali’s example should inspire us to let our own light shine in the world by welcoming opportunities to foster the well-being of others without boasting about it or needing the admiration of endless “thumbs up”, to validate your virtuous character.

Citations/References

Berman, J. Z., Levine, E. E., Barasch, A., & Small, D. A. (2015). The Braggart’s dilemma: On the social rewards and penalties of advertising prosocial behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 52(1), 90–104. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.14.0002

Seneca (est 2016). Letters From a Stoic. Vegeo Press. Translated by Richard Mott Gummere.

My Italian Secret: The Forgotten Heroes. A 2014 documentary written by Oren Jacoby.